Drought: it's a reality for the warm, Mediterranean climatic region of California, especially as human land use changes the landscape and greenhouse grasses trap heat.

Drought can affect plants in many ways. On a physiological level, lack of water produces stress, which can inhibit plant growth and reproduction. Some plants change in appearance or stature under drought stress, often remaining small in size or limiting fruit set, like what might have happened to the Gilia on the left below. Some plants' foliage may wilt, shrivel, and/or die back, like the discoloring manzanita on the right.

In the face of annual "droughts" during the summer months, many species in California have evolved to be "drought deciduous", meaning they die back in the summer and resume growth and reproduction after winter and spring rains. The iconic species black sage (Salvia mellifera) and California sagebrush (Artemisia californica), for example, are drought deciduous and will often turn brown and lose their leaves in the hot summer months. Still, these plants can be negatively affected by long-term droughts. Too many drought years in a row can kill individuals of even these hardy, well-adapted species.

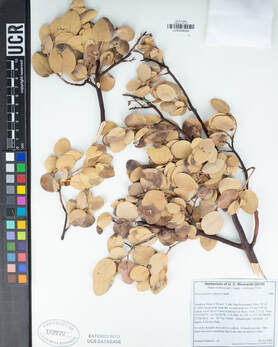

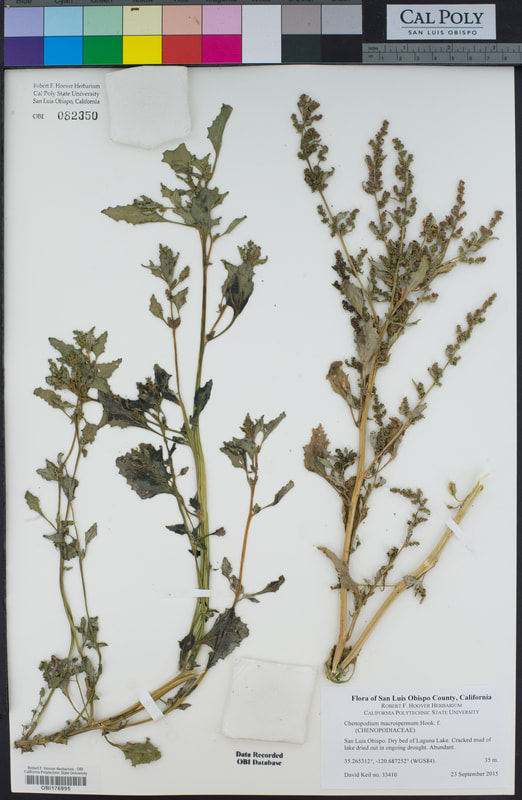

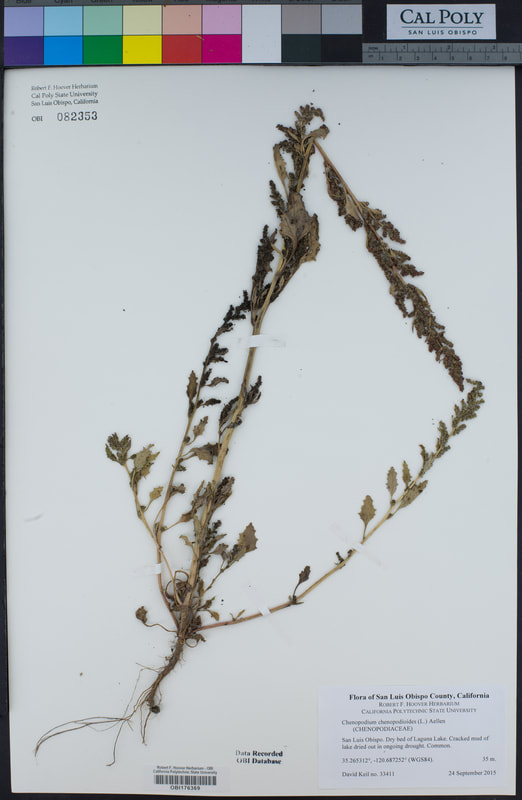

Drought can also alter plant communities, for example, by allowing drought-tolerant, often "weedy" species to take advantage of the open real estate and weakened competition. The specimens below serve as striking examples; as Laguna Lake in San Luis Obispo shrunk into a cracked, dry bed during the 2012-2016 California drought, three different species of opportunistic goosefoot (Chenopodium) sprung up abundantly in its absence.

Other species can temporarily (or permanently) disappear in the face of ongoing drought, as one astute collector noted in some of her collections. She discovered populations of the native annual "clustered tarweed" (Hemizonia/Deinandra fasciculata) the year after the severe drought of 2002, even though the species was "not seen at all in 2002 during severe drought year" (check out the specimen here!).

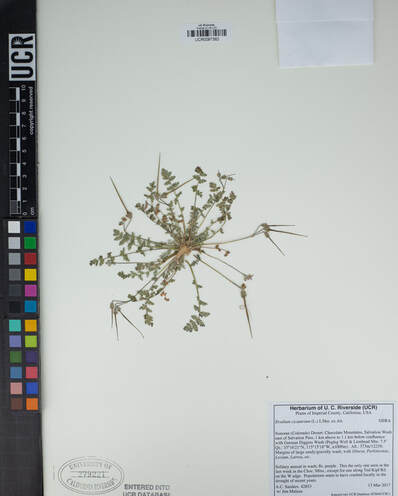

| Sometimes even aggressive, non-native species succumb to the lack of water, as captured on the label of this specimen. Here, Dr. Andy Sanders of the UC Riverside Herbarium (a California Phenology Network collaborator!) discovered that populations of the widespread non-native, redstem stork's bill (Erodium cicutarium) "seem[ed] to have crashed locally in the drought of recent years." Drought can shift the dominance of certain species, alter species abundances as individuals of some species die off from stress, and even drive extirpation of species when the climate becomes too unfavorable. While many plant species have adapted to long periods without water (think cacti, succulents, and deep-rooted oaks), many others have not been able to evolve quickly enough to face the oncoming tide of climate change. |

Herbarium specimens document botanical changes and can help us understand the changing distributions of plants as environmental factors shift, as demonstrated by the examples above. We're so lucky to have such a dedicated community of collectors and botanists who are creating and caring for this resource.