It can be hard to imagine Greater Los Angeles as anything other than the bustling, vibrant, hot, and smoggy metropolis that it currently is. The massive LA metropolitan area is home to some 12.8 million people packed into a sprawling 4,850 square miles dominated by roads, buildings, suburban developments, apartment complexes, and parking lots. But what did it used to look like? Without herbarium specimens, we may have never known.

We may not know in detail what flora and fauna inhabited this lush valley when it was home to Tongva and Chumash tribes prior to the 1550s, but colonial expansion takes time. Western botanists documented plant life in LA basin ecosystems as early as the 1800s, bequeathing us hints of previous ecosystems that are long since buried or past.

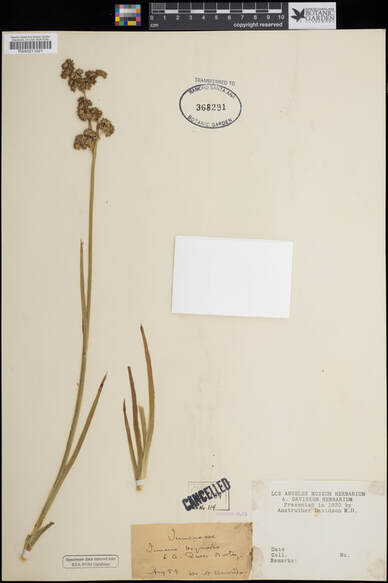

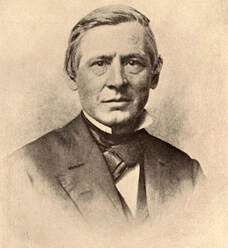

Take, for example, this historical specimen of pointed rush (Juncus oxymeris) collected in 1889 by Scottish-American doctor and botanist Anstruther Davidson.

Like many of its kin, pointed rush is a denizen of wetland places (classified as a “facultative wetland” species by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service), preferring damp meadows and swales across the western United States (USDA, NCRS 2020; Zika 2015). This is hardly habitat one may associate with LA’s palm trees and oak-lined hills, yet historically, much of the LA basin was wet meadows and marshes (Dark et al. 2011; Grossinger et al. 2011) fed by the ocean and the once free-flowing Los Angeles and San Gabriel Rivers. With urbanization and taming of these once mighty (and often flooding) rivers into concrete channels, alluvial floodplains diminished and wetlands were drained, leaving little habitat for water-dependent species like the pointed rush.

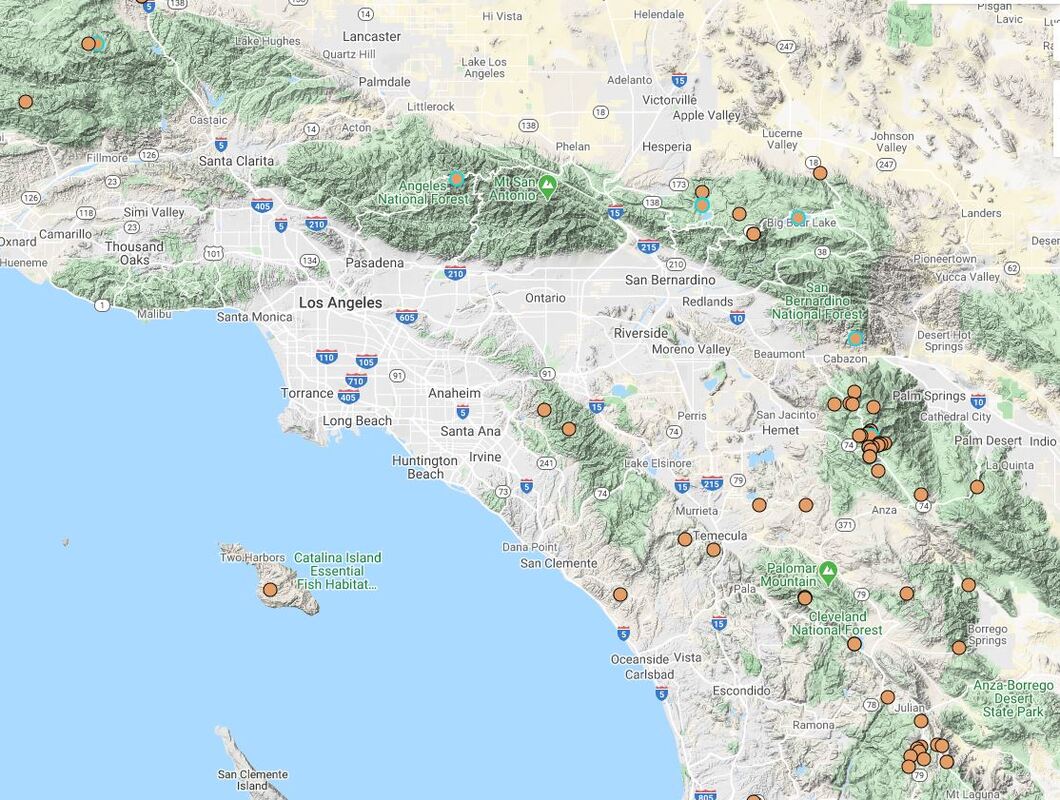

Indeed, there are few reports of pointed rush in the Greater LA area since these early collections. A handful of specimens were collected in the nearby Orange County Saddleback region in the late 1920s to early 1930s, but since then, collections of this species have only been made in the surrounding region, largely in hilly meadows and creeksides far removed from the bustle of the city.

The historical record provided by herbarium specimens is truly irreplaceable. Without these collections, we would have only a dim understanding of the history of life in urbanized areas.

References

- Dark S, Stein ED, Bram D, Osuna J, Monteferante J, Longcore T, Grossinger R, Beller E. 2011. Historical ecology of the Ballona Creek Watershed. Southern California Coastal Water Research Project – Technical Repot #671. https://www.ballonahe.org/downloads/non_geo_data/ballona_report[email].pdf

- Grossinger R, Stein ED, Cayce K, Askevold R, Dark S, Whipple A. 2011. Historical wetlands of the Southern California Coast: An atlas of US coast survey T-sheets, 1851-1889. Coastal Conservatory. http://ftp.sccwrp.org/pub/download/DOCUMENTS/TechnicalReports/589_SoCalTsheetAtlas.pdf

- USDA, NCRS. 2020. The PLANTS Database. Juncus oxymeris Englm. National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401 USA. Accessed 25 February 2020. https://plants.sc.egov.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=JUOX.

- Wikipedia. Greater Los Angeles. Accessed 25 February 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greater_Los_Angeles

- Zika PF. 2015. Juncus oxymeris, in Jepson Flora Project (eds.) Jepson eFlora, Revision 3. Accessed 25 February, 2020. https://ucjeps.berkeley.edu/eflora/eflora_display.php?tid=29699