One of the most essential pieces of data captured by an herbarium specimen is where the plant was found. Herbarium specimens underlie our understanding of where plants occur on this big, green planet. Aggregation of specimen data on large scales, enabled by mass digitization projects (e.g., our own California Phenology Network), can furthermore help us determine why plants occur where they do (Loiselle et al. 2008) and how distributions are changing (Wolf et al. 2016). Building a map of plant distributions across time and space, however, is no simple feat.

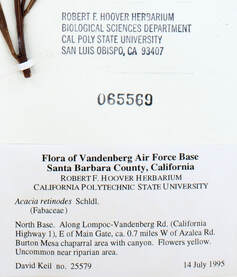

| Because specimen collection is a centuries-old practice, the majority of plant specimens were collected before GPS capabilities were widely accessible. As a result, the location data of millions of specimens remains trapped in a textual description of the location, unavailable for mapping or modeling. This is why georeferencing—determining latitude and longitude coordinates of plant locations from textual descriptions—is a vital step in digitization. Georeferencing can be like a scavenger hunt, requiring consideration of geography, topography, collection practices, and historical context to determine the precise location describe on the specimen label. The process is also very rewarding. The resulting data empowers novel research and helps fill the gaps in our understanding of plant life on Earth. |

Although collaborators and volunteers in the California Phenology Network remain scattered and largely at home during this global pandemic, we are making huge advances in georeferencing California collections. The graphic below shows the georeferencing progress of just one collection, the Cal Poly Hoover Herbarium, from February to June, 2020. Over 1500 specimens were georeferenced during these few short months, and the numbers only continue to grow.

Locations of georeferenced specimens from the Cal Poly Hoover Herbarium over time. Black dots indicate all California specimens georeferenced as of February 2020, and additional colors indicate new georeferences as of the months indicated as follows: Red = March 2020, Blue = April 2020, Green = June 2020

This success is largely made possible by dedicated students, staff, and volunteers, but there is always a need for more help. Volunteers from all over the state—and beyond!—are joining the georeferencing community and contributing to this significant effort. Can you help us fill in the gaps?

Glossary

- Digitization - the process of converting analog data (such as written text) into a digital format (such as word-processed, computerized text)

- Georeferencing - the process of assigning latitude and longitude coordinates to an object given, e.g., a textual description of the location

References and Further Reading

- Bloom TDS, Flower A, DeChaine EG. 2017. Why georeferencing matters: Introducing a practical protocol to prepare species occurrence records for spatial analysis. Ecology and Evolution. 8(1):765-777. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ece3.3516

- Flannery MC. 2017. Georeferencing. Herbarium World: Exploring herbaria and their importance. [Blog] https://herbariumworld.wordpress.com/tag/georeferencing/#:~:text=It%20is%20important%20to%20know,certain%20radius%20of%20that%20point.

- Loiselle BA, Jørgensen PM, Consiglio T, Jiménez I, Blake JG, Lohmann LG, Montiel OM. 2008. Predicting species distributions from herbarium collections: Does climate bias in collection sampling influence model outcomes? Journal of Biogeography. 35(1):105-116. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2007.01779.x

- Wolf A, Zimmerman NB, Anderegg WRI, Busby PE, Christensen J. 2016. Altitudinal shifts of the native and introduced flora of California in the context of 20th-century warming. Global Ecology and Biogeography. 25:418-429. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/geb.12423