As the California Polytechnic State University herbarium team embarked on digitizing their collection, the Robert F. Hoover Herbarium, they came upon a recurring theme: hundreds of the yet un-digitized specimens told of a far-away place called "Ovamboland." This led to some obvious questions: where is (or was) Ovamboland, and why do we have so many specimens from this mysterious place? Notes from Nature volunteers may have asked these same questions as they have transcribed over 4000 specimens from the Cal Poly Hoover Herbarium.

Where is Ovamboland?

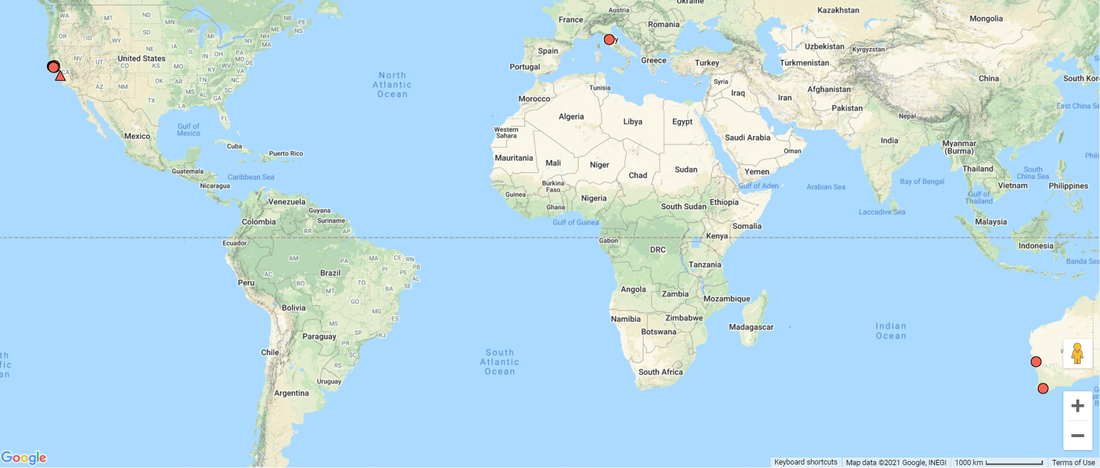

| Fortunately, for these questions, we have the internet. Some quick research revealed that Ovamboland was a territory in the extreme north of modern-day Namibia, home to multiple Ovambo people groups. Ovamboland was established as a self-governing state in 1968 by the South African government, which had took it upon itself to administer all of southwest Africa during the Apartheid era. Ovamboland as a formal territory was dissolved with the independence of Namibia in 1989, though the old name of this region is still generally understood [1]. |

Why does the Cal Poly herbarium have so many specimens from Ovamboland?

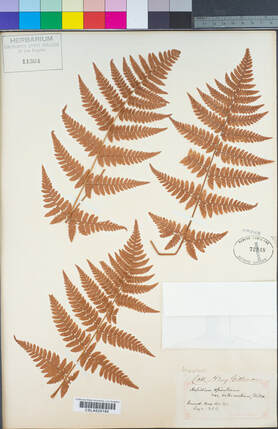

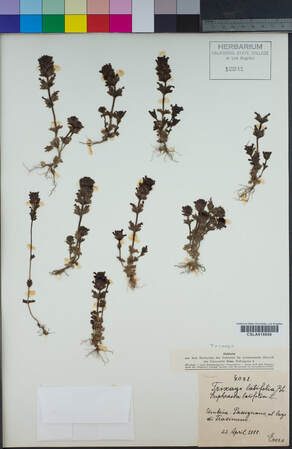

The flora of Ovamboland is featured in the Cal Poly Hoover herbarium due to the work of Robert J. Rodin, an accomplished botanist with an impressive resume of exploration. Born a Californian, Rodin was stationed in Guam and China while serving in WWII, explored southern Africa as a postdoc, worked as a professor in West Pakistan for several years (during which time he made forays into the Himalayas), spent a year as a Fulbright Professor in Delhi (India), and participated in a National Geographic Expedition to Ovamboland. Rodin was a botany professor at Cal Poly for 23 years, from 1953-1976, and as such, he loaded the herbarium with specimens from his travels and studies.[2]

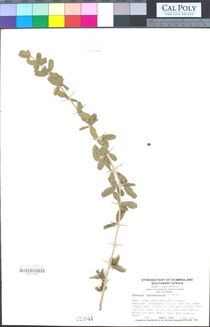

One of Rodin's specialties was the ethnobotany of Ovamboland. Accordingly, many of his specimens from the region include the Kwanyama (a local language) name for the plant and descriptions of how the locals use the plant. These notes are fascinating windows into the culture of the Ovambo people and speak to a rich relationship of the people with their natural resources. Some species were used as remedies for nosebleeds, swelling, and infertility. Others found uses as arrow shafts, fences, or in the construction of huts.

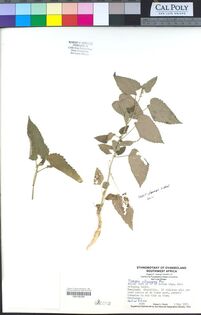

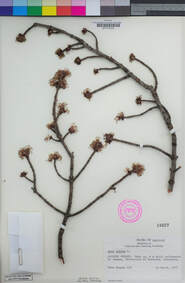

| Other notes on specimens portray unique relationships of people and plants beyond usage as food, medicine, and tools. Take for example, this African endemic shown to the right: Tragia okanyua, a stinging nettle of the Euphorbiaceae (rather than the Urticaceae, as in the worldwide "stinging nettle" native to Europe). Rodin reports that, in Ovamboland, "If children will not herd cattle or do their work, parents threaten to rub this on them." Now that's a unique form of punishment! |

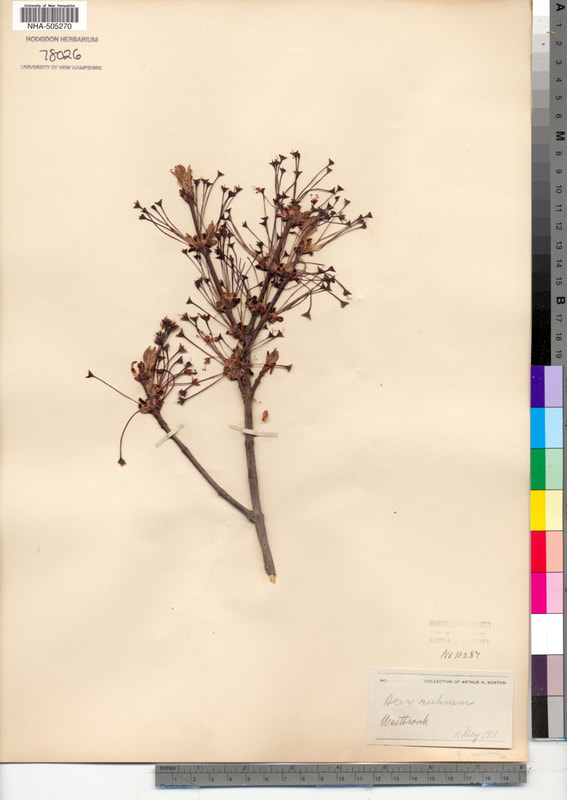

| The notes on the specimen to the left describe semi-supernatural beliefs or uses of plants. Rodin reports, "If you have lost something, carry a stick of this and you will find the lost item. If you hit this plant with a stick, you will have a fight with someone." Plants are not just objects of consumption, but also integral in other aspects of peoples' lives. They're sought out, admired, consulted, and sometimes avoided for a plethora of reasons (like this particular plant...we won't go into detail about why men try not to touch it. But the note tells all!). Ovamboland, while unique it its flora and specific plant-people relationships, is not unique in the importance of plants in the lives of humans. |

Thanks to Robert Rodin and many others, we have the privilege of learning how other people around the globe view and treasure their natural resources. These notes remind us that no matter where you are, we as humans are unified in our dependence on plants.