As catalogs of physical plant specimens, herbaria are fantastic resources for identifying unknown plants, and this utility isn't just for scientific studies or simple curiosity. Sometimes plant identification is a matter of life or death.

Some herbaria receive samples from herders, farmers, or citizens concerned with the potential poisoning of livestock or pets. Because many plants can be poisonous, identification of unknown plants in grazing areas or farmland can be an important preventative (or investigative) measure to prevent the loss of life. Dr. Alison Colwell, curator of the UC Davis Herbarium, and her team, are frequently called upon to identify plants suspected of animal poisoning. She explains:

"Because UC Davis has a veterinary medical school with a diagnostics program, the herbarium gets referrals when animals are thought to be poisoned by plants, this can happen several times a week, mostly in the summer. There are certain plants that recurrently cause grazing animal poisoning, notably Amsinckia and Plagiobothrys in the spring, and Lupinus seeds in early summer, so I’m starting to know the Who’s Who of poisonous plants in California. Ideally, the owner of the affected animals will go around and pick the remainder of the nibbled plants and send them in. Sometimes we get a big bouquet of everything in the pen/corral/field. Often they will just send photos and if those are in focus and include diagnostic features, we can often do an ID from the photo, but we prefer fresh material to confirm ID against our herbarium specimens under the scope, as we have a very good collection of weedy and toxic species here. Sometimes we get part of a bale of hay and have to pick through it to find the weeds, we keep large plastic pans for that messy procedure. The most challenging ID is the contents of the gut of dead livestock, which is both fragrant and fragmentary. The toxicology folks kindly rinse off the plant parts before sending the sample over, but it will still smell a bit. I’ve come to recognize the odor of the contents of a rumen.

| One thing that I’m getting concerned about is animal poisonings from oleander relatives (Apocynaceae). This has been goats so far, as owners tend to clip their shrubbery and feed it to their pet goats. Goats can eat a lot of things and do OK but they cannot survive ingesting the compounds in oleander and its relatives. Most Californians are aware of the toxic properties of oleander (Nerium oleander), but there are tropical relatives that are getting popular in horticulture, especially southern California, where it doesn’t freeze. Among these are yellow oleander (Cascabela thevetia/Thevetia peruviana). I’ve seen this deadly plant for sale at garden centers with no warning on it at all! |

This part of my job is causing me to see landscaping in a different way – these days when I’m walking down a city street, I’m starting to see the plants in terms of their toxicity instead of their attractiveness!

Herbarium staff and other botanists use their knowledge, reference texts, and physical herbarium specimens to conduct this identification process. Not only are herbarium specimens a crucial reference for identification, but they are also used to document the establishment, distribution, and spread of potentially poisonous plants across history.

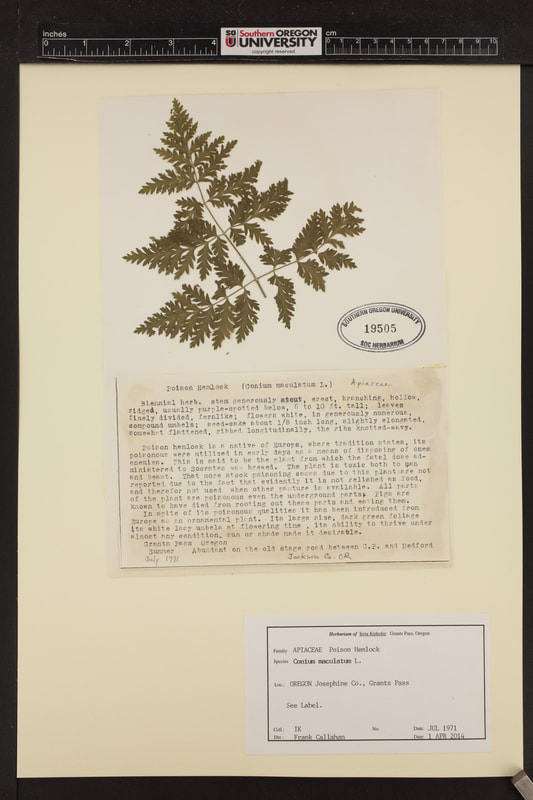

Take for example, the specimen below. On the (especially detailed) note, the collector of this plant chronicled the saga of poison hemlock. He notes, "The plant is toxic both to men and beast...." and "...In spite of its poisonous qualities it has been introduced from Europe as an ornamental plant." Poison hemlock is now widespread across the United States (just look at the distribution of this species across California in this map!). Knowing where it came from, the habitats it inhabits, and its potential pattern of spread may help us prevent it from spreading further and help us seek out where it may have quietly become established. There's no replacement for a robust herbarium record of plants, native and introduced.

By the way, did you notice that this specimen hails from the Southern Oregon University? Political boundaries weren't drawn with natural biomes in mind, and a large chunk of the the California Floristic Province is found in southwestern Oregon. To ensure the best possible coverage of the CFP, our friends at the Southern Oregon University Herbarium are now serving a copy of their data in CCH2. This has brought 22,000 new specimens to the CCH2, along with 20,000 images like the one shown above. California herbaria aren't the only ones collecting, digitizing, and curating these resources; the herbarium community is broad and more interconnected than ever in our work to catalog, protect, and promote biodiversity.