You can do a lot of science with 3 million herbarium specimen records.

By making our digitized specimen data available not only through the CCH2 portal, but also through global aggregators GBIF and iDigBio, researchers across the world can view and use this valuable resource for studies in their fields. Research topics vary from species endemism and distributions, to invasive species, to human health and fire ecology. In this and upcoming blog posts, we will highlight recently-published papers from research communities outside of California that nevertheless use data from California herbarium specimens to explore and explain our natural world in new and exciting ways.

Patterns of diversity of American alpine species

Figueroa, H.F., Marx, H.E., de Souza Cortez, M.B. et al. Contrasting patterns of phylogenetic diversity and alpine specialization across the alpine flora of the American mountain range system. Alp Botany (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00035-021-00261-y

| One of the great questions facing biologists is "how do biological communities assemble?", in other words: "how did all these species come to live in this same place?" This research published in Alpine Botany by PhD student Hector Figueroa of University of Michigan, and colleagues, focuses on this very question for the unique plant communities of alpine regions. |

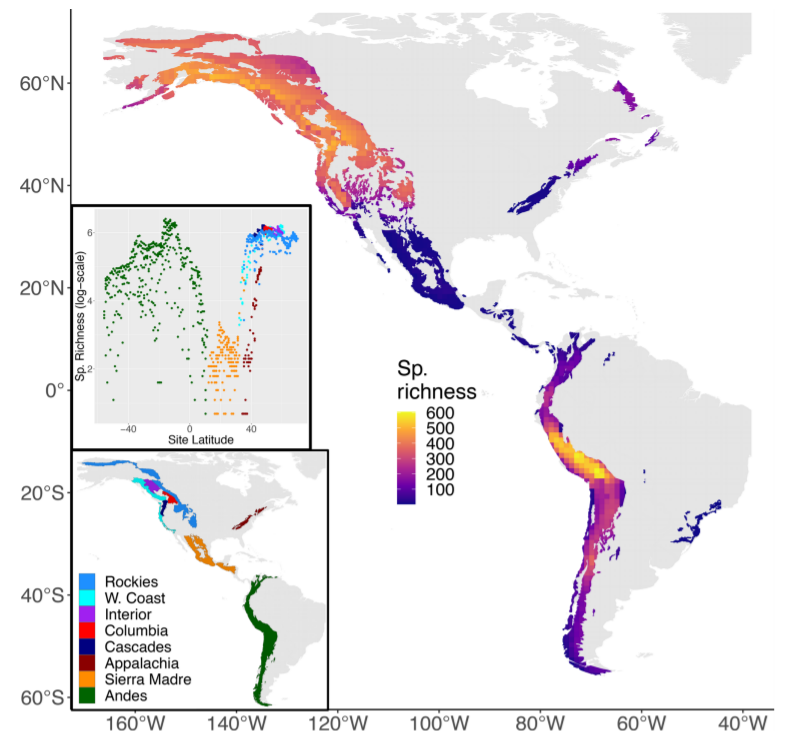

Alpine ecosystems are characterized by inhospitable abiotic conditions; bitter cold, high UV exposure, harsh winds, and rocky, eroding soil are just a few factors that plant species in these areas have faced over evolutionary time. Despite this, thousands of species (2,937 of which are included in this paper) have evolved to live in these environments, and Figueroa et al. wanted to understand how they came to be. Figueroa et al. used species distribution models to compare patterns of diversity due to phylogenetic (i.e., evolutionary relatedness) and abiotic factors. They found that different alpine communities across the Americas—for example, Patagonian versus Rocky Mountain communities--showed different patterns of diversity, suggesting that each region assembled due to unique factors. In other words, harsh climatic conditions alone don't necessarily determine which species can exist in an area, yet assembly does not depend solely on species being at the right place at the right time (the history-filtering hypothesis). They also found that species richness did not follow a simple latitudinal gradient (species in other environments and taxonomic groups have been shown to display a latitudinal gradient in species richness, with highest diversity around the equator).

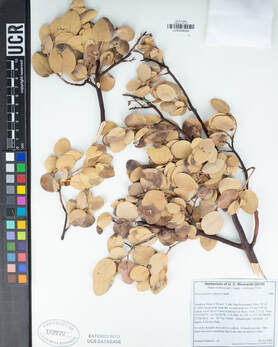

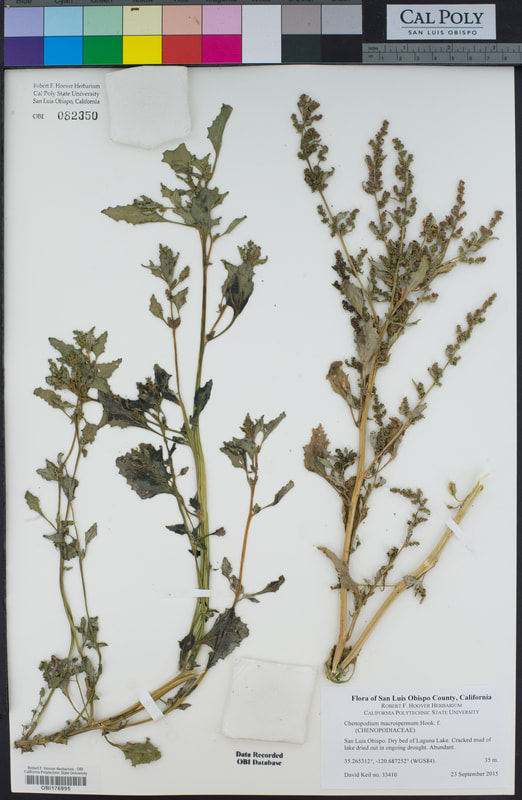

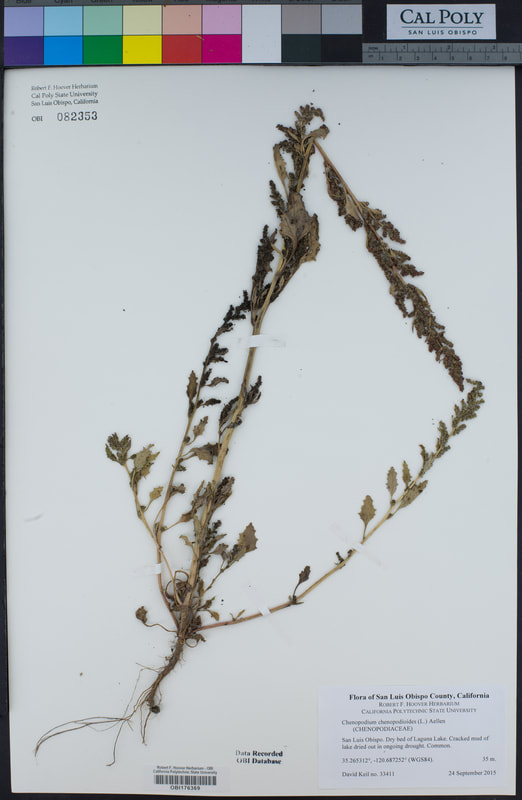

This work represents an important use of millions of herbarium specimen records to answer a foundational question in evolutionary biology; and many hundreds of thousands (over 600,000, to be more precise) of these specimens originated from our very own California herbaria! The dataset included specimens from the San Diego Natural History Museum Herbarium, UC Riverside Herbarium, CSU Chico Herbarium, Robert F. Hoover Herbarium at Cal Poly State University, and several others. California herbaria play an important role in shaping our understanding of global evolutionary patterns.

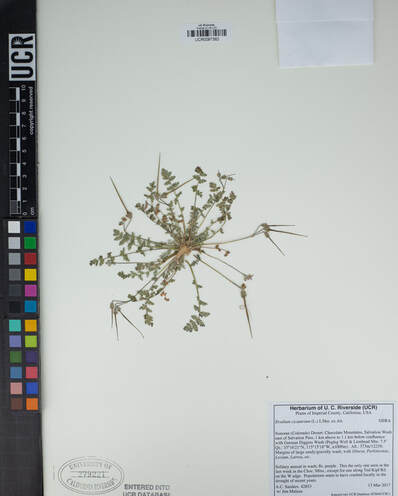

| Specimen of the alpine plant Penstemon davidsonii likely included in the dataset used by Figueroa et al. to create species distribution models. Prior to the CAP project, the originating herbarium, Cal State LA, was 0% digitized. The project has liberated this unique collection to contribute to such broad-scale analyses. |

Glossary

- Aggregator - organization that gathers data from multiple sources and makes them accessible from a single site. The Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) and iDigBio are two major aggregators of natural history specimen data.

- Assembly - the process of species moving/evolving over evolutionary time, resulting in the communities of species we see co-occurring today

- History-filtering hypothesis - the scientific hypothesis that phylogenetic and biogeographic factors primarily influence the assembly of communities

- Species richness - the number of species found in a particular region