Herbaria are far from static collections of dead plants; with the ongoing activity of botanists, curators, and volunteers, herbaria can be dynamic archives of plant life in this era of rapid anthropogenic change. One such significant change documented by herbarium specimens is the introduction of exotic and potentially invasive species--like the newly documented orchid that may have traveled across the U.S. from Florida all the way to California!

But before we talk about invading orchids, let's get one thing straight: how can herbarium specimens document change?

First, herbarium specimens are used to study how non-native plant species have historically invaded novel regions, as well as what characteristics can make a plant invasive and potentially detrimental to native ecosystems. For example, scientists at Butler and Auburn Universities used herbarium specimens to learn that some invasive species in Indiana got loose by escaping from cultivation (Dolan et al. 2011). Another study found evidence that some species that reproduce sexually may be more invasive than plants that primarily reproduce asexually (Lambrinos 2001). Researchers can look at where and when non-native species were collected and determine whether there are predictable patterns in the data.

|

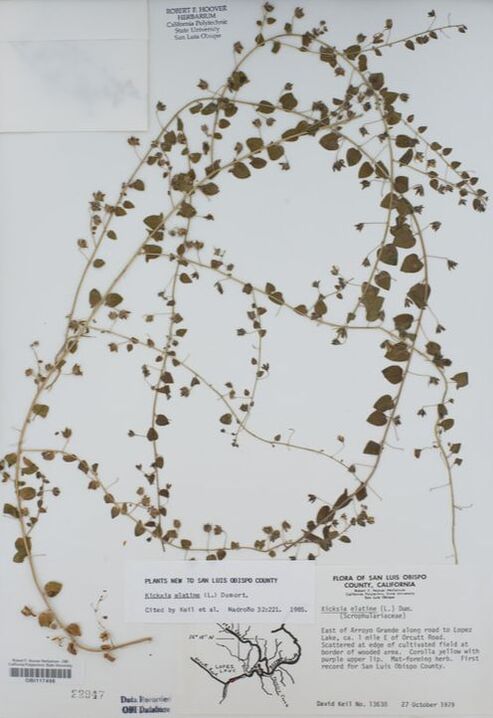

Second, herbarium specimens are tangible evidence for new introductions as they occur; they can be the first documentation of a species being found in a new place. Take, for example, this specimen of sharpleaf cancerwort (Kickxia elatine) collected in 1979. Native to Eurasia, this (admittedly adorable) herb has spread across the United States as an occasionally noxious weed. Collector David Keil, a renowned California botanist, noticed this new species for the area and collected this specimen as early evidence of invasion. With this documentation, other botanists, conservationists, and land managers can know to be on the lookout for this potentially threatening species.

|

So, where does the non-native orchid come in? The story is similar to David Keil's cancerwort discovery, but with even more observers. Earlier this month, members of the Orange County Chapter of the California Native Plant Society noticed a strange new plant growing in a road median in Long Beach.

Botanists took to the investigation. They collected and identified the newcomer as centipede grass orchid (Zeuxine strateumatica), a native of Asia that has become a nuisance in the southeastern U.S. This species had never previously been found in the L.A. Basin and was first collected in the western U.S. only a few years ago in 2017 (Bell & McNeill 2016). Now, we have physical evidence of this plant's introduction into California in the form of carefully preserved herbarium specimens. One of these specimens was collected by one of the California Phenology Network's principal investigators, Amanda Fisher, who also documented the finding on iNaturalist, an app for documenting observations of plants and animals. No photo can substitute for the physical plant itself, however, which will be carefully safeguarded and studied as evidence of our changing world.

Glossary

- anthropogenic - caused by or initiated by humans

- asexual reproduction - reproduction that occurs without the combination of gametes, such as by producing clonal shoots

- noxious weed - plant taxon that has been designated by a governmental or other entity to be harmful to crops, native ecosystems, or livestock

- sexual reproduction - reproduction that occurs with the combination of gametes, such as that facilitated by flowers

References / Further reading

- Bell DS, McNeill R. 2016. Zeuxine strateumatica. Crossosoma 42(2):93-94.

- Dolan RW, Moore ME, Stephens JD. 2011. Documenting effects of urbanization on flora using herbarium records. Journal of Ecology. 99:1055-1062.

- Lambrinos JG. 2001. The expansion history of a sexual and asexual species of Cortaderia in California, USA. Journal of Ecology. 89:88-98.

- Pearson KD, Mast AM. 2019. Mobilizing the community of biodiversity specimen collectors to effectively detect and document outliers in the Anthropocene. American Journal of Botany. 106(8): 1052–1058. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6851561/pdf/AJB2-106-1052.pdf