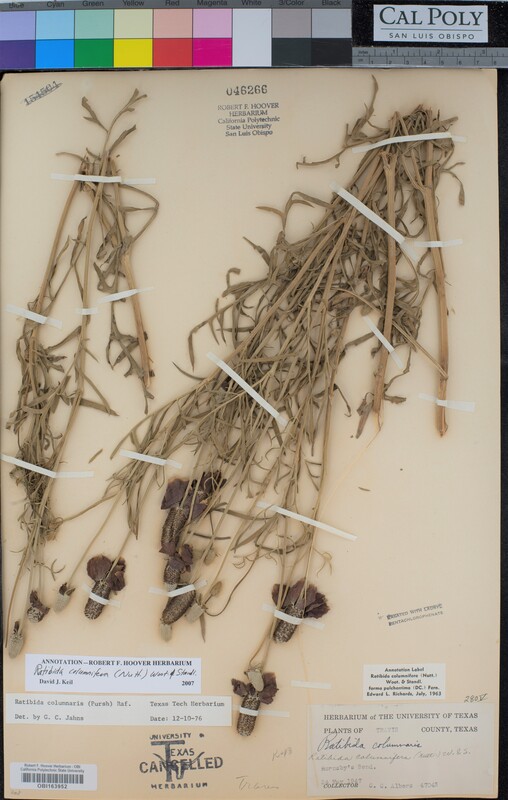

Every specimen is different, but some really stand out amidst the thousands. Below is a specimen of prairie coneflower, Ratibida columnifera, that we discovered that struck us with its unique assortment of labels and stamps. What do they all mean? This specimen, like all others we've digitized during the CAP project, is a historical document and artefact, and its markings and labels illustrate the many phases in a specimen's (hopefully) enduring existence.

Let's first start chronologically, with the original specimen label in the bottom left corner of the record. This label records that the specimen was collected by one C.C. Albers in 1947, only two years after the end of World War II. Despite the fact that this botanist collected over 47,000 specimens, we couldn't find much about him. The name likely refers to Carl Clarence Albers, potentially a professor in pharmacy at the University of Texas (see this article in the University of Texas alumni magazine) who also collected plants and worked in plant taxonomy (see this comparative study of the genus Monarda). CCH2 only has 32 specimens collected by Albers to date (including several Monardas), though the SEINet network includes over 1,800. Clearly additional digitization is needed to discover more about his collecting efforts.

Either Albers or another botanist identified the specimen as Ratibida columnaris or Ratibida columnifera—exactly which hand-scrawled name came first on the original label is unclear—but at some point, both names were listed on the label because Ratibida columnaris is no longer the accepted taxonomic name. In 1963, an Arkansas botanist and expert on the genus Ratibida, Edward L. Richards. identified the specimen as a specific form (forma) of the species. Ratibida columnifera f. pulcherrima is the red-petaled form of the species (and currently a popular wildflower in horticulture !).

In 1976, a Master's student named Gary Charles Jahns (look at his type-written thesis!) re-identified the specimen to Ratibida columnaris, which may have been the current accepted name due to existing evidence at the time. However, in 2007, the plant was re-annotated back to R. columnifera by David Keil, then the director of the R.F. Hoover Herbarium at Cal Poly.

Why all these changing names? Are botanists really so contentious? Well, yes and no: names for species and the specimens that represent them can change for many reasons, including changes to whether a species name is accepted or labeled as a synonym of some other species. Changes in taxonomic names usually occur because more data have been collected or data have been re-analyzed. For example, genetic data gathered from specimens can help researchers identify major splits in a species, or highlight the genetic similarities among specimens that may warrant collapsing multiple species into one. Whatever the case for this specimen, its identity as Ratibida columnifera has lasted since 2007, but there is always room for collecting more evidence.

Two more important markings on this specimen may pique your curiosity: the stamp on the bottom right that reads "Treated with lauryl pentachlorophenate", and the University of Texas CANCELLED stamp in the bottom center.

Lauryl pentachlorophenate, also known as pentachlorophenyl laurate, was a widely used insecticide and fungicide in herbaria in the 1960s and beyond to prevent pest and fungal damage to specimens. Unfortunately, at the time, the health effects of this dangerous chemical were unknown (one article even said it was "harmless to humans"! Whitmore 1965). The chemical was sprayed on the specimens was was very effective at protecting the plants from damage. However, it was later identified as acutely toxic and a carcinogen, yet another example of how continued research and data collection can and should change our previously-held views. This insecticide (and in fact, most insecticides) are no longer used in most herbaria.

Lastly, why the big "CANCELLED" stamp? This University of Texas stamp shows us that this specimen was transferred between herbaria. Herbaria are constantly exchanging and gifting specimens with the goal of diversifying their collections, sharing knowledge, and decreasing the likelihood that one particular set of specimens gets destroyed. This process has been active for centuries and is why you find specimens like this beautiful coneflower, potentially collected by a pharmacy professor at the University of Texas, in a modest collection on the Central Coast of California 85 years later. History is documented on the pages of these specimens.

Glossary

form/forma - a taxonomic rank below the rank of variety, often indicating a specific growth form or habit of the species that may be location-specific